For more information on American politics (1960-1970), see: https://www.alternatehistory.com/fo...rnative-cold-war.280530/page-15#post-10759150

===

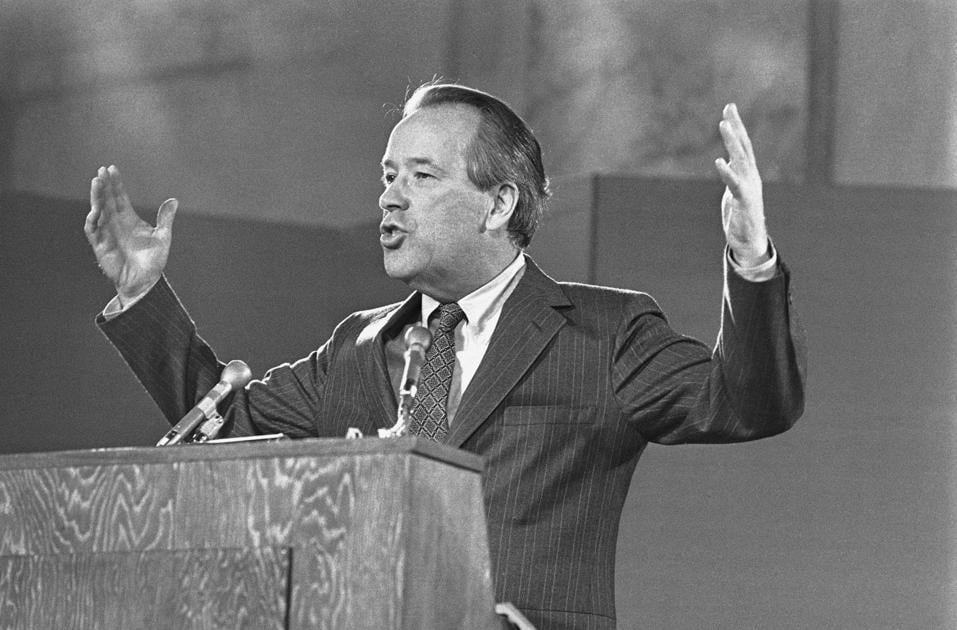

Henry M. "Scoop" Jackson, President of the United States, represented to many of his supporters the virtues of an America pushing forward into the future. A first-generation American, the son of Norwegian immigrants who had settled in Washington state (his father's surname had originally been "Gresseth" but had been changed to sound more 'typically American'), Jackson had climbed up the ranks of American society seemingly through merit, studying at Stanford and the University of Washington School of Law. Working as a prosecutor after passing the bar, Jackson eventually was elected to Congress in 1940 and would be undefeated in congressional elections until eventually being selected as the Democratic nominee and winning the 1968 presidential election. To many Americans, Jackson seemed like the perfect counterpoint to his Republican predecessor, "Chuck" Percy. Percy's doveish policies had concerned many Americans, who constantly read in newspapers and saw on television new crises and an anaemic response to the extension of Communist power throughout the world. Even non-Communist regimes such as the United Arab Republic were nevertheless threatening American interests. They saw many nations of Western Europe wavering as they lost faith in the willingness of the United States to defend their territories from Soviet Russia. At home, whilst there had been progress on civil rights issues, there still existed many reactionaries who sought to block or rollback further progress towards a more equitable American society. Scoop Jackson had been a career-long liberal but he nevertheless had the tough-on-crime bona fides from his past as a prosecutor and the hawkish foreign policy required to win over many conservative patriots. It was for these reasons that Jackson was nominated once again as the Democratic candidate in the 1972 presidential election, despite being probably the most liberal major figure left in the Democratic Party since the 1970 mid-terms solidified the drift of conservative Republicans to the party which had, in living memory, established the New Deal; and the concomitant defection of liberal Democrats to the G.O.P. Running against recent defector to the Republicans, George McGovern, and once again against Progressive Party candidate Wayne Morse. Between the three presidential candidates, this was arguably the most liberal presidential election in United States history to that point; however Jackson chose as his running mate conservative Dixiecrat Strom Thurmond. Thurmond had publicly moderated his stance on race, which in the past had been pro-segregation, but maintained a great deal of legitimacy amongst conservatives of the South. Whilst George McGovern did manage to do well in several Midwestern states (largely due to his pro-farmer policies), the Jackson-Thurmond ticket was able to prevail in the South and much of the Northeast. Notably, Morse was able to win Jackson's home state of Washington, but the Progressives were unable to win any state outside of the Pacific Northwest. Nevertheless, their share of the popular vote in Republican-held states was slowly but surely increasing, reinforcing the belief that the third party was here to stay.

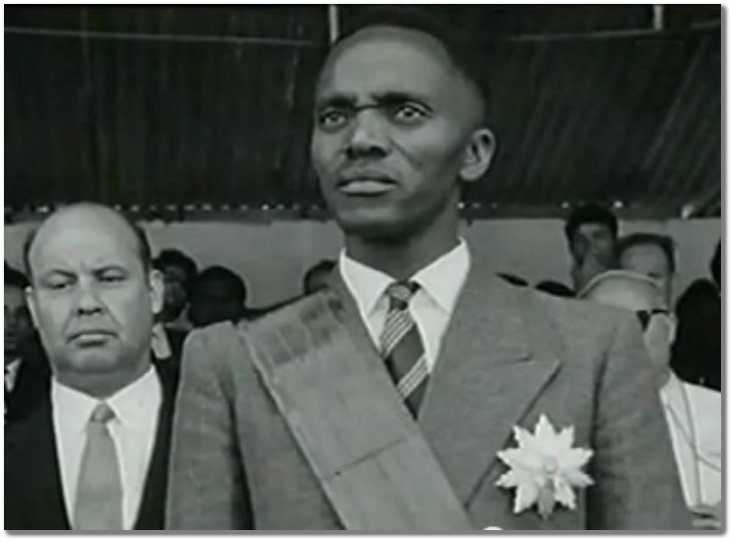

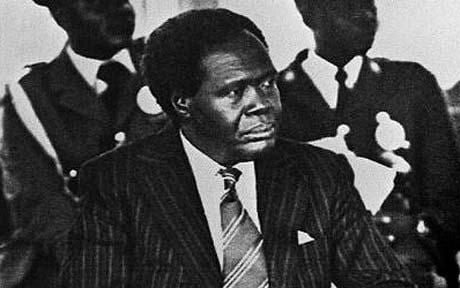

Henry M. "Scoop" Jackson, US President 1968-1976

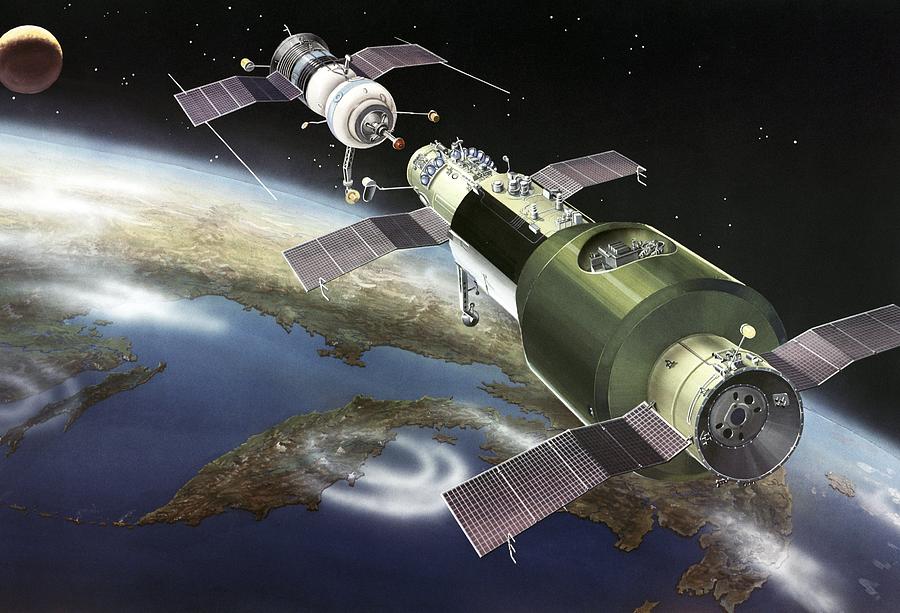

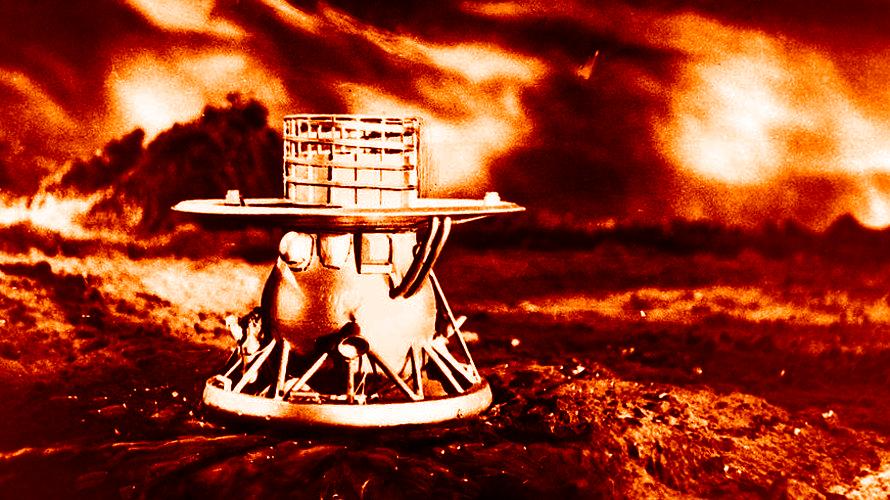

In his second term as President, Jackson continued to promote environmental legislation (although this often excluded logging due to close contacts in the logging industry) with mixed success. Relative to his first term, where he had been able to pass through a number of initiatives such as an increase in the intake of educated immigrants and promoting the construction of air travel infrastructure nationwide (no doubt this would have been welcomed by his allies in the aerospace industry), as well as the promotion of the technical sciences in education, his second term gave him less room to maneuver regarding domestic policy. Whilst his party had supported him in order to secure the presidency, his views were increasingly out of step with the consensus among the more right-ward leaning Democratic Party. As such, many of his pet projects were unable to get effective support, as his own party would often reject them, and Republicans who would otherwise be supportive of the policies didn't want a Democrat taking credit for them. As such, and knowing that this would be his last term, Jackson looked to foreign policy to define his legacy. Looking to maintain a technologically-advanced and robust military force, Jackson continued to promote the aerospace industry. His tenure was noticeable for limiting the production of long-range bombers but developing a large and advanced nuclear missile strike capacity; whilst America had spent much of the 1960s moving away from long-range bombers after the Goldsboro and Thule Incidents, Jackson diversified the nuclear strike capabilities of the United States, promoting a large nuclear attack submarine fleet and the continued development of MIRVs. Jackson was also instrumental in repairing relations with the French military junta. Whilst he couldn't convince the French and their neighbours to rejoin NATO, he did arrange and agreement whereby both alliances would have a permanent attache to the other, and would cooperate on military exercises. A particularly welcome olive branch that Jackson extended to the French was a technology-exchange programme with the French, despite some trepidation amongst the American military brass that they couldn't protect against Communist infiltration of French intelligence; Jackson retorted by saying the Russians would probably have an easier time infiltrating the American military. According to him all the communists in France were in one place; jail. Jackson's liberalism left him with little love personally for the European juntas, but he rationalised it as all part of being a superpower... many allies are unsavoury but necessary. With the focus of the Cold War superpower contest having shifted from Europe to the so-called "Third World", Jackson promoted good relations with the Andean Community of Nations, decreasing the US strangehold on the economies of many South American nations. This earned him a number of enemies within the intelligence community, especially the CIA. Where Jackson and the CIA did not differ on policy was in the promotion of economic development for US allies in Africa. Whilst the French and Italians maintained a great deal of influence in Tunisia and Libya, the United States provided generous aid packages for US-aligned states such as Morocco, Ethiopia, Benin, Biafra and Yorubaland. Under Jackson's leadership, the United States also turned a blind eye to South African and Rhodesian activities in Southern Africa. In Asia, the focal point of Jackson's policy was the maintainance of the US partnerships with Japan and the Philippines, as well as the solidification of an American alliance with Bharatiya to provide a South Asian counterweight to China's power in East Asia.

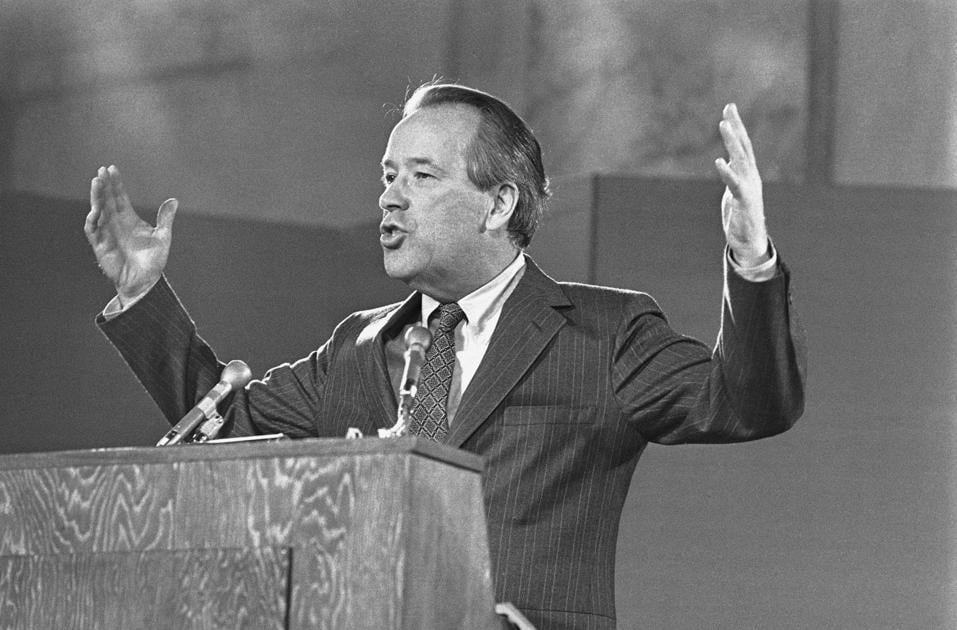

1974 saw the passing of Progressive Party leader Wayne Morse. His successor would be Mark Hatfield, who had been Morse's running mate in the 1968 election. Hatfield's personal political beliefs were fairly eclectic. He was in many respects very socially liberal, opposing abortion and the death penalty. He also strongly believed in economic growth, particularly centred around community-focused investments. Mark Hatfield would select Minnesota governor Wendell R. Anderson as his running mate. The Progressive ticket was still unable to truly challenge the two major parties, but the Hatfield-Anderson campaign continued the Progressive Party's upward electoral trajectory. However, the split in the liberal electorate between the Progressives and Republicans would allow the Democrats to maintain control of the White House in 1976. The 1976 election saw the Progressives perform well in the Northwest and parts of the Midwest. The Republicans, who put forward McGovern once again, with Edmund Muskie as his running mate, successfully took much of the Northeast. The Democratic Party put forward as their champion Alabama governor George Wallace, with Barry Goldwater as his running mate[193]. Wallace had claimed that he no longer supported segregation (a cause that by 1976 had been long dead) and that he was not a racist but had a long record of racist campaign advertisements in his gubernatorial campaigns. Barry Goldwater had found Wallace's racism personally very off-putting, but as a recent defector from the Republican party lacked the institutional connections to directly contest Wallace as a presidential candidate[194]. With the liberal voting base split between Hatfield and McGovern, the Wallace-Goldwater ticket was able to narrowly win the election, winning in the Deep South, parts of the Midwest and the American Southwest, including California as well as Michigan. Alongside official campaigning, the Wallace-Goldwater ticket had also benefitted from widespread grassroots promotion of their ticket from white supremacist groups such as the White Citizen's Councils and hyper-conservative organisations, for instance the John Birch Society.

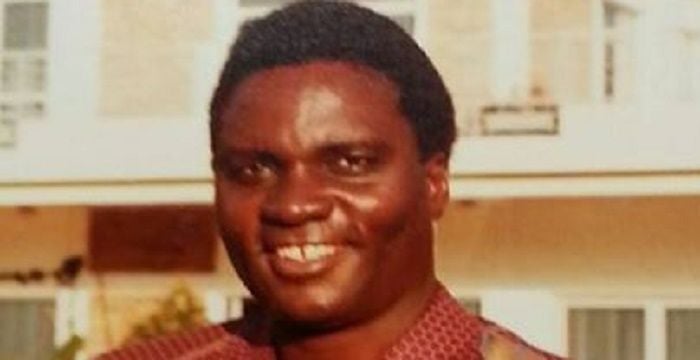

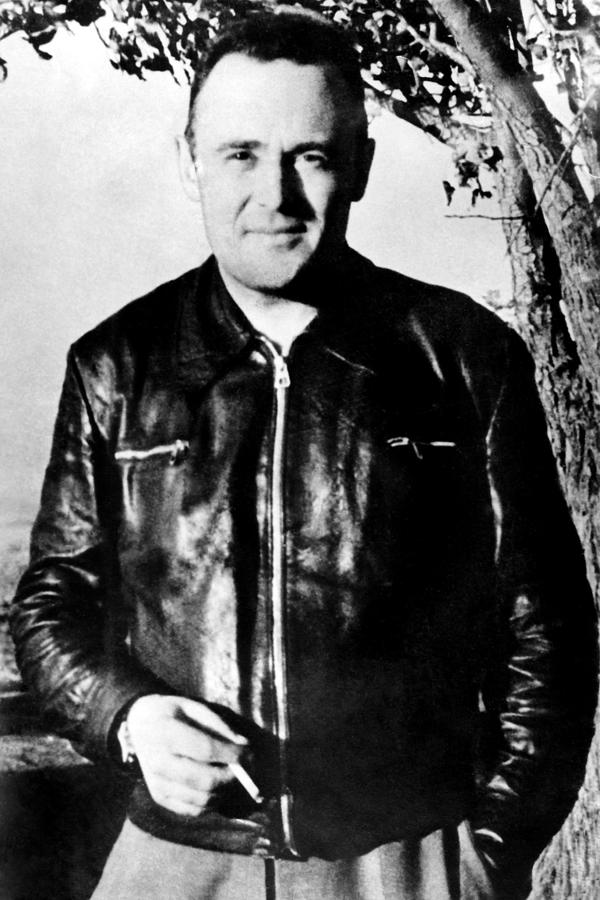

Future President of the United States George Wallace, 1970

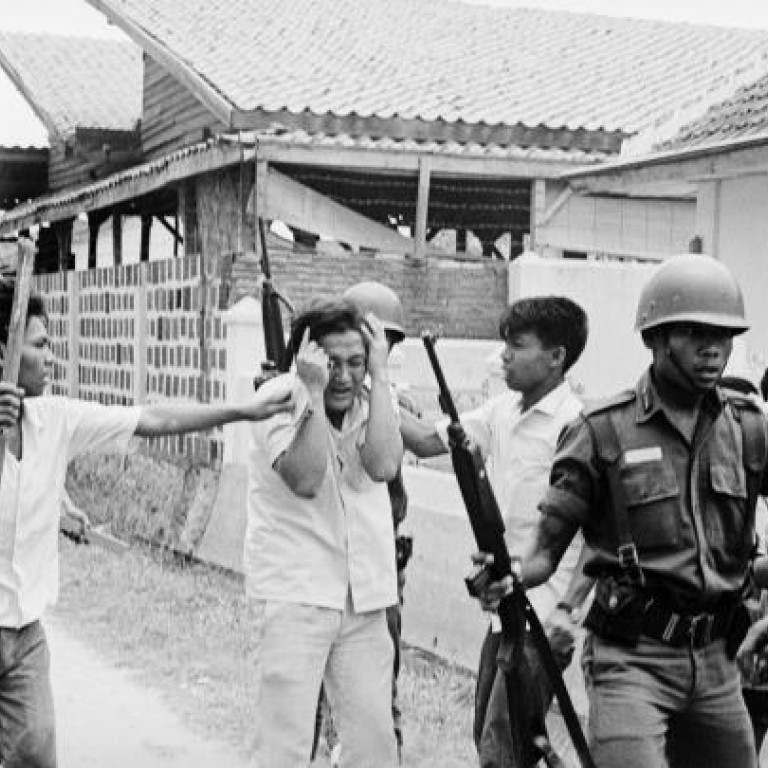

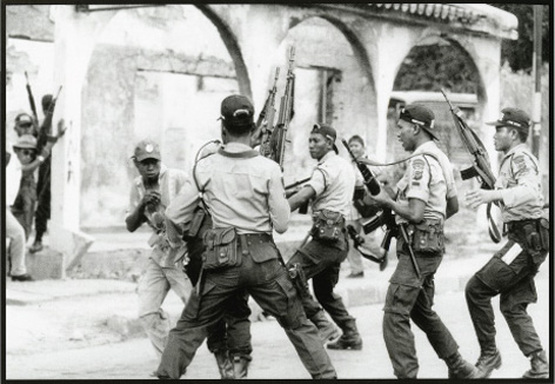

President Wallace would institute a number of populist policies, including increases in social security and Medicare. He also tried to reduce the influence of the federal government which did in the short term reduce infrastructural development. Decreases on tax for low and medium-income workers also boosted his popularity, albeit at the expense of reducing government coffers. Wallace also removed the price controls on oil that had been maintained by Jackson throughout the early 1970s. Under Wallace, the pace of the liberalisation of society largely halted. The strongly conservative Wallace also pushed against radical minority ethnic organisations such as the American Indian Movement, Black Panthers and Brown Berets. In later years, his active involvement in the suppression of radical groups has come under criticism, as personal communications to higher-ups in the FBI encourage the use of extrajudicial violence against activists. For the most part, Wallace had little interest in foreign policy. He sought to encourage the leaders of US allies to take greater responsibility for funding their own defence; in particular he praised the French junta for taking their continent's destiny into their own hands. Wallace maintained a good relationship with the South African and Rhodesian government. When criticised from this, he simply denounced "commie pinkos who refuse the peoples of South Africa and Rhodesia their right to keep free from Communist tyranny!". The major foreign policy shift of the Wallace administration was the rapprochement with the United Arab Republic. Influenced by a number of notable anti-Semites in his former gubernatorial campaign, Wallace reduced support for Jewish interests in the Middle East. He also took advantage of growing discord in the relationship between the UAR and USSR as a result of continued Soviet support for communist parties in the UAR, as well as differences of agreement over policy regarding South Yemen, the Gulf and Iran. Oil prices in the United States dropped with an increase in supply due to the UAR exporting large volumes to America.

===

[193] IOTL, George Wallace was shot in an assassination attempt in 1972. He was shot four times, with one lodging in his spinal column and leaving him paralyzed from the waist down. ITTL the bullet that lodged in his spine hits him elsewhere, leaving him injured but not paralyzed. He thus has a better chance campaigning (looking less fragile) and gains a reputation as "bulletproof Wallace" amongst supporters. I also believe that this butterflies away his supposed religious awakening which in later years curbed his racism (or so he claimed).

[194]IOTL, in 1964 Wallace offered to defect to the Goldwater campaign if named running mate. ITTL that is butterflied away, and theres a reversal of the situation. IOTL Goldwater rejected the offer due to Wallace's racism, but ITTL he's desperate for a political opportunity and takes the opportunity of being Wallace's running mate.

===

Henry M. "Scoop" Jackson, President of the United States, represented to many of his supporters the virtues of an America pushing forward into the future. A first-generation American, the son of Norwegian immigrants who had settled in Washington state (his father's surname had originally been "Gresseth" but had been changed to sound more 'typically American'), Jackson had climbed up the ranks of American society seemingly through merit, studying at Stanford and the University of Washington School of Law. Working as a prosecutor after passing the bar, Jackson eventually was elected to Congress in 1940 and would be undefeated in congressional elections until eventually being selected as the Democratic nominee and winning the 1968 presidential election. To many Americans, Jackson seemed like the perfect counterpoint to his Republican predecessor, "Chuck" Percy. Percy's doveish policies had concerned many Americans, who constantly read in newspapers and saw on television new crises and an anaemic response to the extension of Communist power throughout the world. Even non-Communist regimes such as the United Arab Republic were nevertheless threatening American interests. They saw many nations of Western Europe wavering as they lost faith in the willingness of the United States to defend their territories from Soviet Russia. At home, whilst there had been progress on civil rights issues, there still existed many reactionaries who sought to block or rollback further progress towards a more equitable American society. Scoop Jackson had been a career-long liberal but he nevertheless had the tough-on-crime bona fides from his past as a prosecutor and the hawkish foreign policy required to win over many conservative patriots. It was for these reasons that Jackson was nominated once again as the Democratic candidate in the 1972 presidential election, despite being probably the most liberal major figure left in the Democratic Party since the 1970 mid-terms solidified the drift of conservative Republicans to the party which had, in living memory, established the New Deal; and the concomitant defection of liberal Democrats to the G.O.P. Running against recent defector to the Republicans, George McGovern, and once again against Progressive Party candidate Wayne Morse. Between the three presidential candidates, this was arguably the most liberal presidential election in United States history to that point; however Jackson chose as his running mate conservative Dixiecrat Strom Thurmond. Thurmond had publicly moderated his stance on race, which in the past had been pro-segregation, but maintained a great deal of legitimacy amongst conservatives of the South. Whilst George McGovern did manage to do well in several Midwestern states (largely due to his pro-farmer policies), the Jackson-Thurmond ticket was able to prevail in the South and much of the Northeast. Notably, Morse was able to win Jackson's home state of Washington, but the Progressives were unable to win any state outside of the Pacific Northwest. Nevertheless, their share of the popular vote in Republican-held states was slowly but surely increasing, reinforcing the belief that the third party was here to stay.

Henry M. "Scoop" Jackson, US President 1968-1976

In his second term as President, Jackson continued to promote environmental legislation (although this often excluded logging due to close contacts in the logging industry) with mixed success. Relative to his first term, where he had been able to pass through a number of initiatives such as an increase in the intake of educated immigrants and promoting the construction of air travel infrastructure nationwide (no doubt this would have been welcomed by his allies in the aerospace industry), as well as the promotion of the technical sciences in education, his second term gave him less room to maneuver regarding domestic policy. Whilst his party had supported him in order to secure the presidency, his views were increasingly out of step with the consensus among the more right-ward leaning Democratic Party. As such, many of his pet projects were unable to get effective support, as his own party would often reject them, and Republicans who would otherwise be supportive of the policies didn't want a Democrat taking credit for them. As such, and knowing that this would be his last term, Jackson looked to foreign policy to define his legacy. Looking to maintain a technologically-advanced and robust military force, Jackson continued to promote the aerospace industry. His tenure was noticeable for limiting the production of long-range bombers but developing a large and advanced nuclear missile strike capacity; whilst America had spent much of the 1960s moving away from long-range bombers after the Goldsboro and Thule Incidents, Jackson diversified the nuclear strike capabilities of the United States, promoting a large nuclear attack submarine fleet and the continued development of MIRVs. Jackson was also instrumental in repairing relations with the French military junta. Whilst he couldn't convince the French and their neighbours to rejoin NATO, he did arrange and agreement whereby both alliances would have a permanent attache to the other, and would cooperate on military exercises. A particularly welcome olive branch that Jackson extended to the French was a technology-exchange programme with the French, despite some trepidation amongst the American military brass that they couldn't protect against Communist infiltration of French intelligence; Jackson retorted by saying the Russians would probably have an easier time infiltrating the American military. According to him all the communists in France were in one place; jail. Jackson's liberalism left him with little love personally for the European juntas, but he rationalised it as all part of being a superpower... many allies are unsavoury but necessary. With the focus of the Cold War superpower contest having shifted from Europe to the so-called "Third World", Jackson promoted good relations with the Andean Community of Nations, decreasing the US strangehold on the economies of many South American nations. This earned him a number of enemies within the intelligence community, especially the CIA. Where Jackson and the CIA did not differ on policy was in the promotion of economic development for US allies in Africa. Whilst the French and Italians maintained a great deal of influence in Tunisia and Libya, the United States provided generous aid packages for US-aligned states such as Morocco, Ethiopia, Benin, Biafra and Yorubaland. Under Jackson's leadership, the United States also turned a blind eye to South African and Rhodesian activities in Southern Africa. In Asia, the focal point of Jackson's policy was the maintainance of the US partnerships with Japan and the Philippines, as well as the solidification of an American alliance with Bharatiya to provide a South Asian counterweight to China's power in East Asia.

1974 saw the passing of Progressive Party leader Wayne Morse. His successor would be Mark Hatfield, who had been Morse's running mate in the 1968 election. Hatfield's personal political beliefs were fairly eclectic. He was in many respects very socially liberal, opposing abortion and the death penalty. He also strongly believed in economic growth, particularly centred around community-focused investments. Mark Hatfield would select Minnesota governor Wendell R. Anderson as his running mate. The Progressive ticket was still unable to truly challenge the two major parties, but the Hatfield-Anderson campaign continued the Progressive Party's upward electoral trajectory. However, the split in the liberal electorate between the Progressives and Republicans would allow the Democrats to maintain control of the White House in 1976. The 1976 election saw the Progressives perform well in the Northwest and parts of the Midwest. The Republicans, who put forward McGovern once again, with Edmund Muskie as his running mate, successfully took much of the Northeast. The Democratic Party put forward as their champion Alabama governor George Wallace, with Barry Goldwater as his running mate[193]. Wallace had claimed that he no longer supported segregation (a cause that by 1976 had been long dead) and that he was not a racist but had a long record of racist campaign advertisements in his gubernatorial campaigns. Barry Goldwater had found Wallace's racism personally very off-putting, but as a recent defector from the Republican party lacked the institutional connections to directly contest Wallace as a presidential candidate[194]. With the liberal voting base split between Hatfield and McGovern, the Wallace-Goldwater ticket was able to narrowly win the election, winning in the Deep South, parts of the Midwest and the American Southwest, including California as well as Michigan. Alongside official campaigning, the Wallace-Goldwater ticket had also benefitted from widespread grassroots promotion of their ticket from white supremacist groups such as the White Citizen's Councils and hyper-conservative organisations, for instance the John Birch Society.

Future President of the United States George Wallace, 1970

President Wallace would institute a number of populist policies, including increases in social security and Medicare. He also tried to reduce the influence of the federal government which did in the short term reduce infrastructural development. Decreases on tax for low and medium-income workers also boosted his popularity, albeit at the expense of reducing government coffers. Wallace also removed the price controls on oil that had been maintained by Jackson throughout the early 1970s. Under Wallace, the pace of the liberalisation of society largely halted. The strongly conservative Wallace also pushed against radical minority ethnic organisations such as the American Indian Movement, Black Panthers and Brown Berets. In later years, his active involvement in the suppression of radical groups has come under criticism, as personal communications to higher-ups in the FBI encourage the use of extrajudicial violence against activists. For the most part, Wallace had little interest in foreign policy. He sought to encourage the leaders of US allies to take greater responsibility for funding their own defence; in particular he praised the French junta for taking their continent's destiny into their own hands. Wallace maintained a good relationship with the South African and Rhodesian government. When criticised from this, he simply denounced "commie pinkos who refuse the peoples of South Africa and Rhodesia their right to keep free from Communist tyranny!". The major foreign policy shift of the Wallace administration was the rapprochement with the United Arab Republic. Influenced by a number of notable anti-Semites in his former gubernatorial campaign, Wallace reduced support for Jewish interests in the Middle East. He also took advantage of growing discord in the relationship between the UAR and USSR as a result of continued Soviet support for communist parties in the UAR, as well as differences of agreement over policy regarding South Yemen, the Gulf and Iran. Oil prices in the United States dropped with an increase in supply due to the UAR exporting large volumes to America.

===

[193] IOTL, George Wallace was shot in an assassination attempt in 1972. He was shot four times, with one lodging in his spinal column and leaving him paralyzed from the waist down. ITTL the bullet that lodged in his spine hits him elsewhere, leaving him injured but not paralyzed. He thus has a better chance campaigning (looking less fragile) and gains a reputation as "bulletproof Wallace" amongst supporters. I also believe that this butterflies away his supposed religious awakening which in later years curbed his racism (or so he claimed).

[194]IOTL, in 1964 Wallace offered to defect to the Goldwater campaign if named running mate. ITTL that is butterflied away, and theres a reversal of the situation. IOTL Goldwater rejected the offer due to Wallace's racism, but ITTL he's desperate for a political opportunity and takes the opportunity of being Wallace's running mate.

Last edited: